Paradise Point and Vacation Village:

A Bit of Tahiti in San Diego

By Martin S. Lindsay

America’s Pastime!

In 1958, semi-retired movie producer Jack Skirball had a new gig — building bowling alleys!

For years, he and his older brother Bill were equal partners in everything they did, including producing Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942) and Shadow of a Doubt (1943), owning and managing theatre chains, real estate investments, and now — the Bowlero family amusement centers. They were building their second (said to be the nation’s largest and most modern) in San Diego.

Old pasturelands around the San Diego River in Mission Valley were being bought up and transformed into new businesses, both modern and Polynesian-themed: Town and Country Hotel, May Company Shopping Center, Hanalei Hotel.

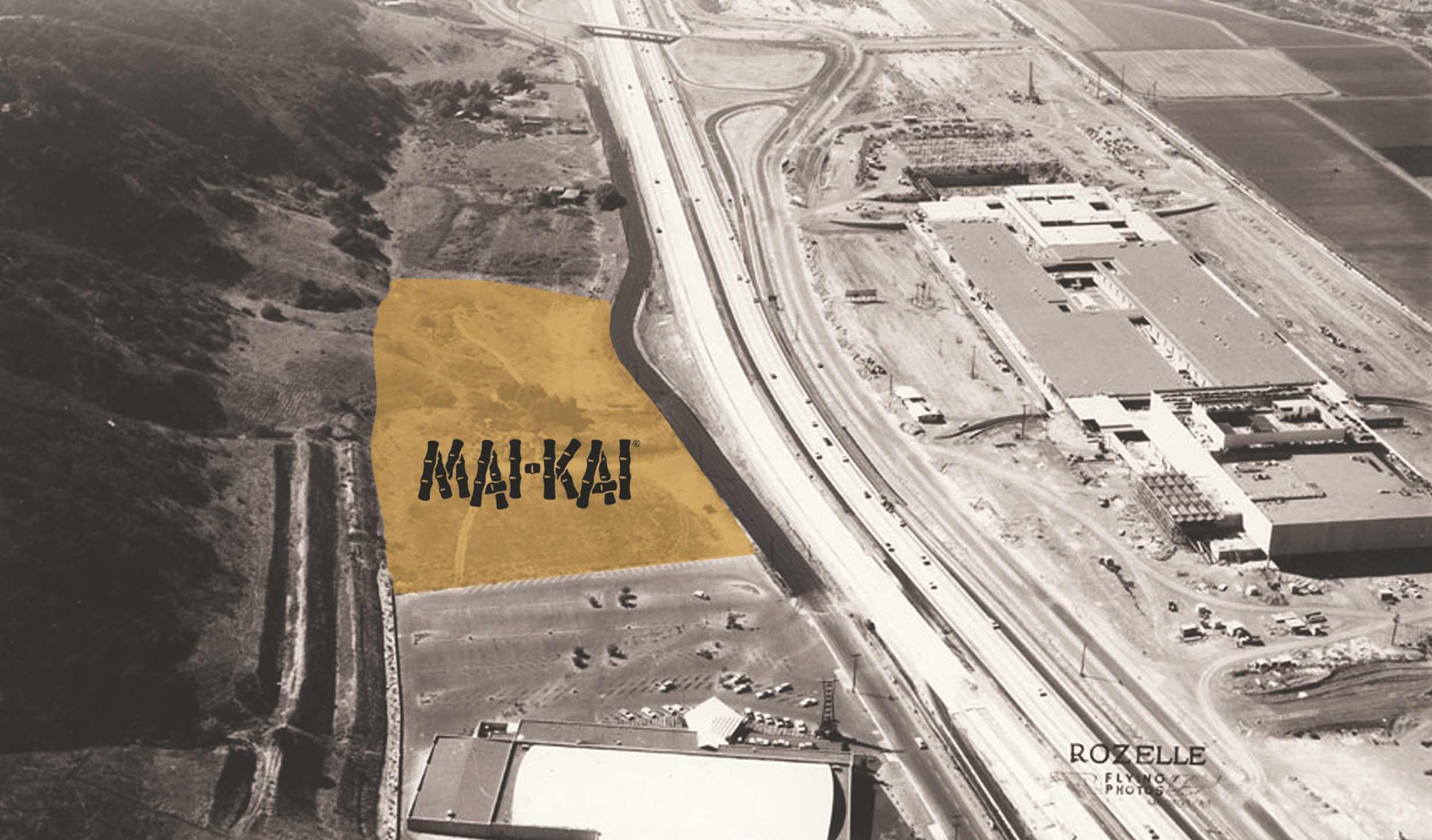

Heck, Jack and Robert Thornton were even looking to build a Mai-Kai restaurant next to the Skirballs’ Bowlero.

“I Wanna Be a Producer!”

Jack Harold Skirball (1895–1985) was the youngest of ten kids and grew up near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Although not a religious man, he entered the rabbinate at an early age. “You couldn’t get buried unless you joined a temple,” he admitted. “I joined because my father died.”

His brothers found employment in the fledgling motion picture industry, working for theatre chains and film exchanges (regional distribution companies that leased exhibition rights to theaters). He joined them, but the young rabbi wanted to make a difference, so with his brothers’ connections, he became a producer of educational films. His first attempt was not that successful.

In 1932 Skirball signed on a young, up-and-coming comedian Bob Hope for two-reel comedy shorts out of his Educational Pictures Studio in Astoria, New York. When columnist Walter Winchell asked the actor how his first film turned out, Hope replied, “I’ll tell you how it was. When they catch John Dillinger, they’re going to make him sit through it twice.” Skirball fired Hope.

But in 1938, he took a chance and produced Birth of a Baby, the first commercial film to show a live human birth. It was commissioned by the American Committee on Maternal Welfare, an organization made up of the nation’s leading medical and child welfare organizations. At the time, 12,000 women per year were dying in childbirth. The committee hoped to lower this number by at least seventy-five percent.

The film was immediately banned in New York and Boston. The April 11, 1938 issue of Life magazine featured a four-page spread with 35 stills from the film. Many other cities banned the issue for indecency, police confiscating all copies they could find and arresting dealers who sold copies. Life’s editor Roy Larsen was arrested and put on trial for obscenity charges.

The media circus made Skirball famous.

A full page devoted to Jack Skirball’s “Birth of a Baby,” scratched microfilm image from The Ottawa Journal, 1942.

Joe Skirball was business manager for director Frank Floyd (Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935) and suggested Jack team up with him to make pictures. Frank and Jack produced films for Universal, starring Claudette Colbert, Joseph Cotten, Bette Davis, David Niven, Ginger Rogers, and John Wayne. They bought the script for Saboteur from David O. Selznick, who loaned them director Alfred Hitchcock, at $150,000 for 18 weeks. While they had him, they also produced Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, with Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotton. During the war years, the government imposed a spending limit of $5000 per film for set construction using new materials. Hitchcock was used to spending $100,000. So the film was shot on location in Santa Rosa.

Wartime restrictions on set construction costs led Alfred Hitchcock to film “Shadow of a Doubt” on location in Santa Rosa, California. Jack Skirball co-produced.

Mission Bay Park

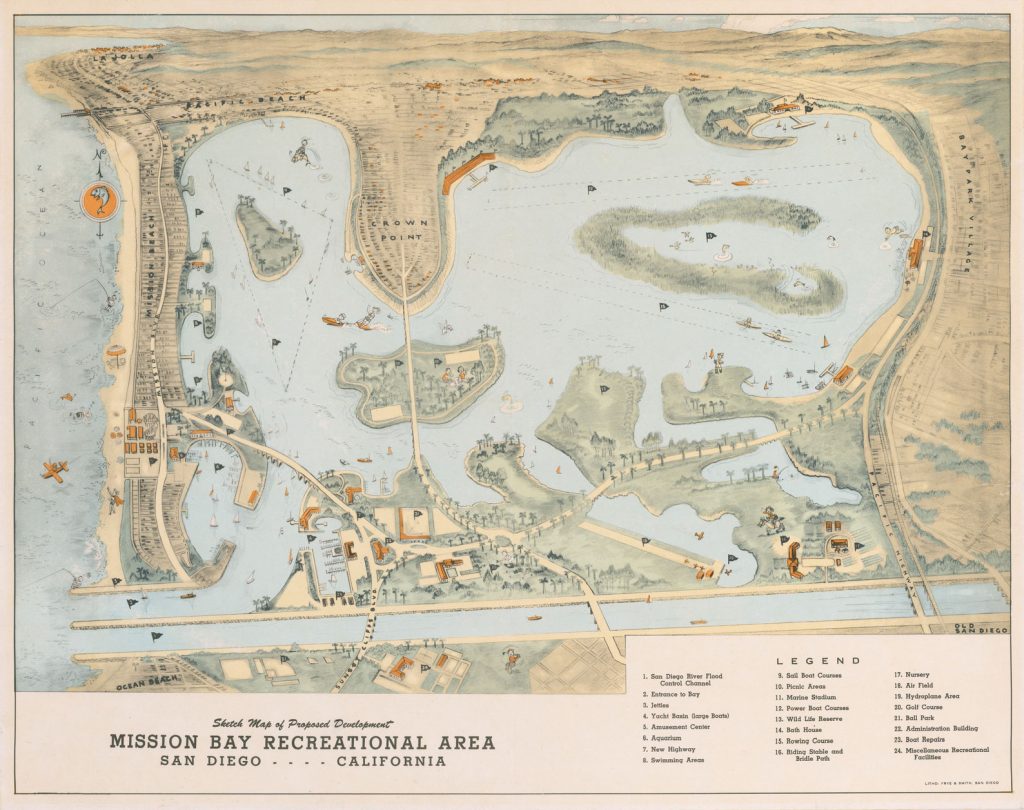

By the 1950s, the San Diego River had been tamed by flood control channels, which rerouted its flow out to the Pacific Ocean, away from the marshlands to the north and downtown to the south.

That swamp to the north was named Bahia Falza (“False Bay”) by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo when he sailed into the area and claimed it for Spain. Cabrillo was commissioned by Antonio de Mendoza, Viceroy of New Spain (Cuba) to explore previously uncharted Alta California coast. On September 28, 1542, his fleet of ships explored the bay and to its north a smaller inlet — too shallow for his boats. By January, he’d be dead at 43 of gangrene due to a shattered shin escaping Tongva warriors on Capitana (Santa Catalina Island). They’d pulled in their ship San Miguel to fix leaks, and were attacked while fetching fresh water. Cabrillo sent a rescue party to get his men. Francisco de Vargas reported that when they rowed to the shore to fetch his men, Cabrillo jumped out of the boat, and “one foot struck a rocky ledge, and he splintered a shinbone.”

Four hundred years later Bahia Falza, too, was being transformed into an oceanfront playland named Mission Bay Aquatic Park. Twenty-five million cubic yards of sand and silt had been dredged to terraform the park. A commission was set up by the City of San Diego to take bids on the park’s commercial development, and the Skirball brothers were all-in.

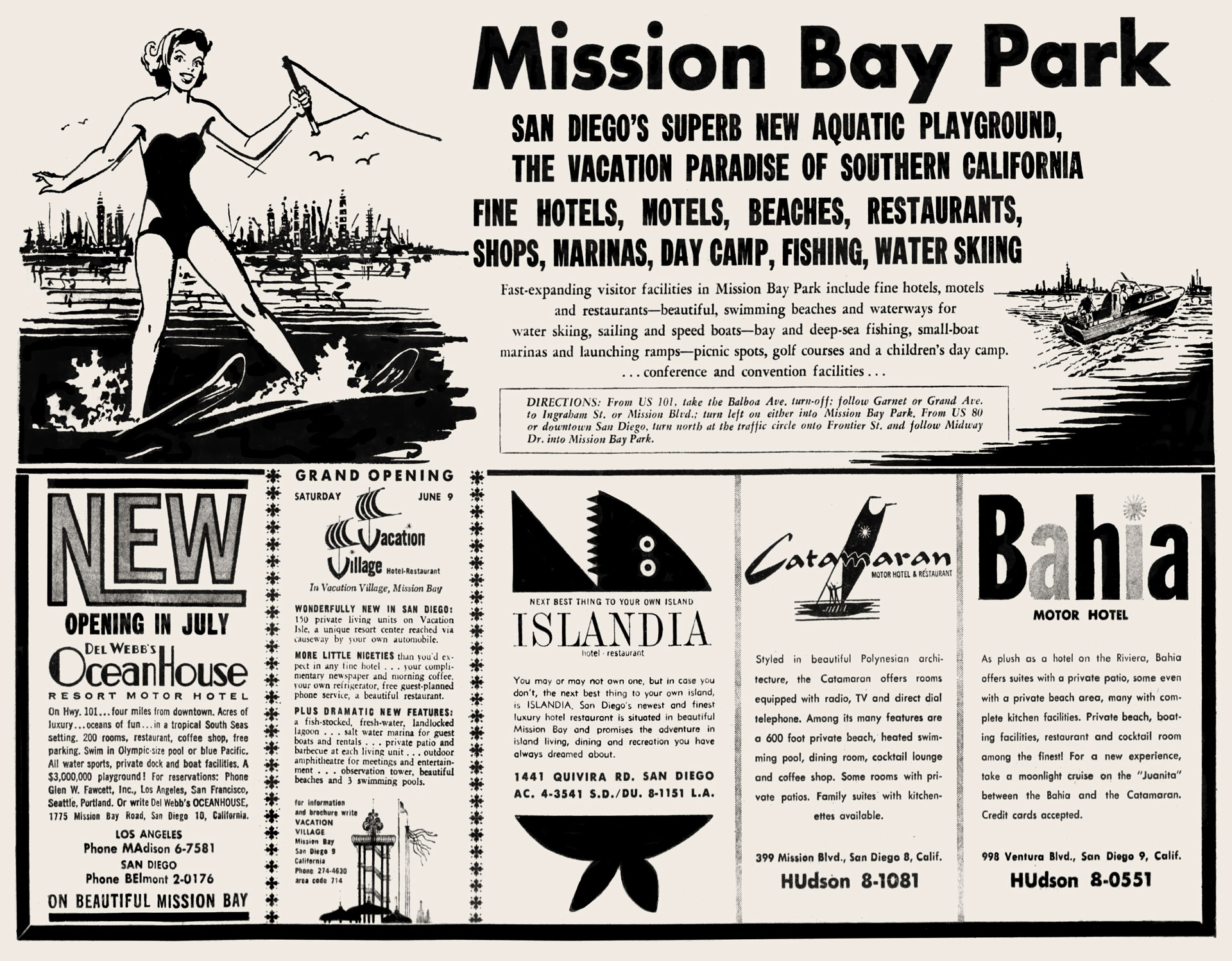

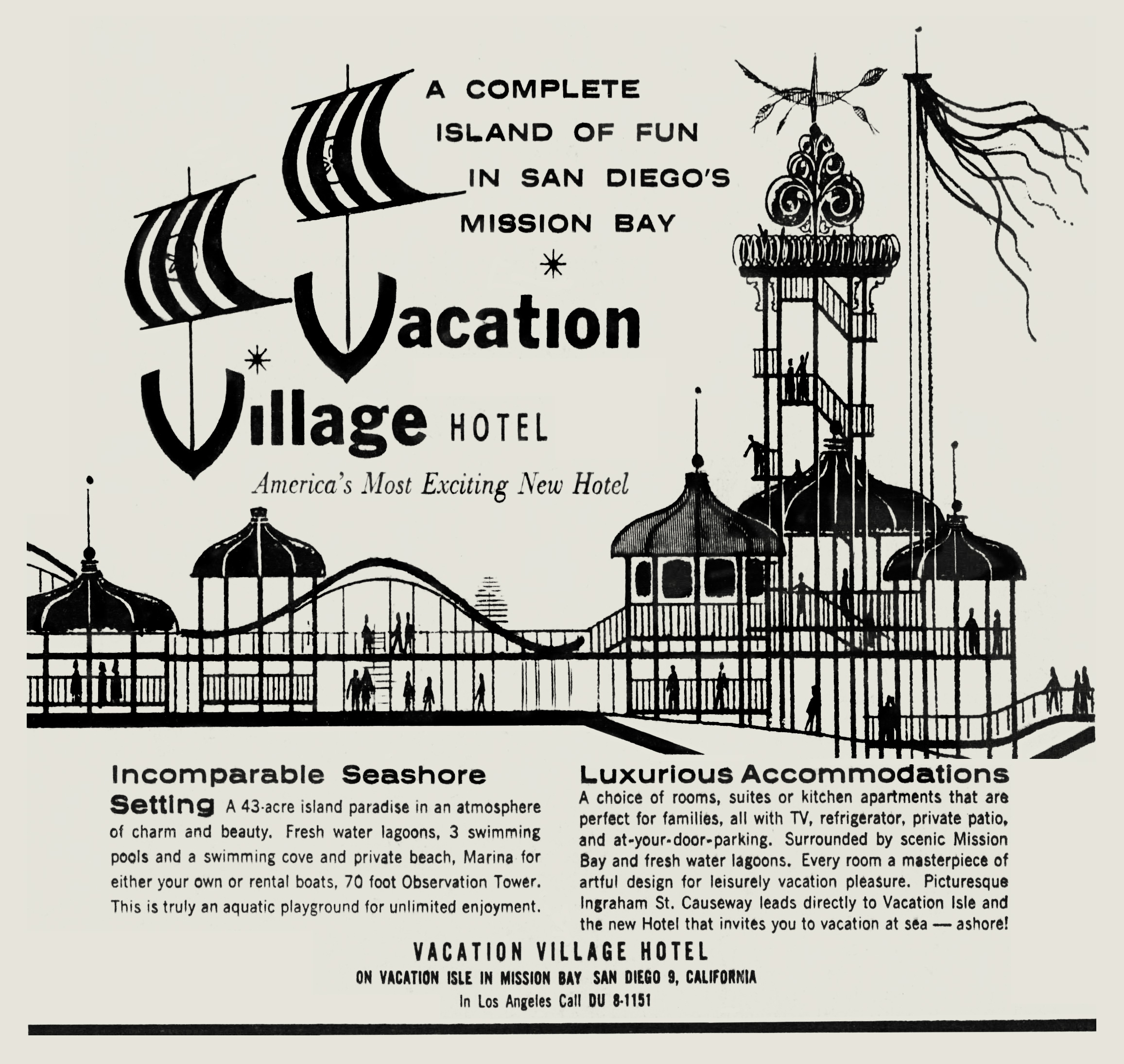

By the summer of 1962, the City of San Diego began promoting Mission Bay to Los Angelenos as a one-stop vacation wonderland. Los Angeles Times, 27 May 1962.

Tierra del Fuego

“I sneaked in here without anybody in my office knowing I was in town,” said Skirball. He chose an empty, sandy, man-made island in Mission Bay named Tierra del Fuego, deciding it was the perfect spot to develop a family resort. He had some crazy ideas, and consultants recommended that he just “put a big hotel on it.” He eventually hired architects Ted Spencer and Alton Salisbury Lee of the San Francisco Bay area’s Spencer & Lee to make his vision come true. “Nobody else understood what I was talking about.”

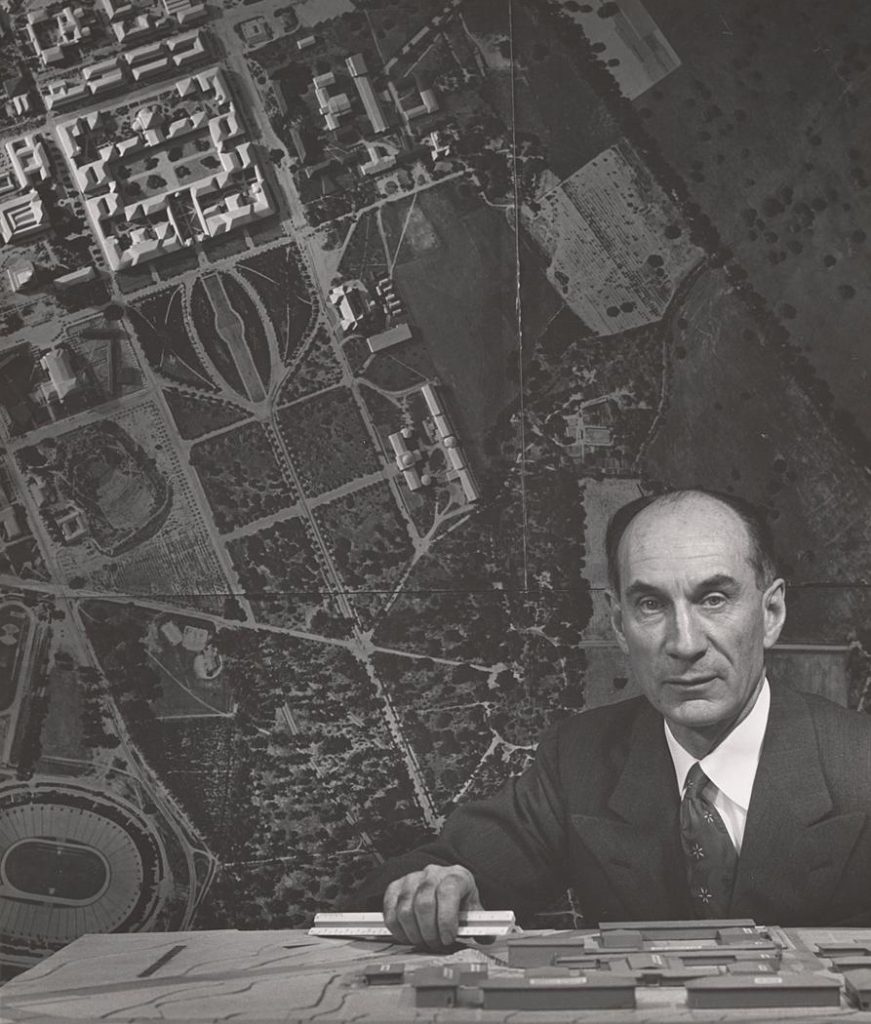

Eldridge Ballard Spencer (1893–1978), who adopted the name “Ted” in the Army during WWI — after Theodore Roosevelt — was known by the 1960s as the “dean of environmental architecture.” In the ’20s and ’30s, Ted and his wife Jeanette Dyer Spencer worked on Yosemite’s Ahwahnee hotel and bungalow cottages. Jeanette designed the hotel’s interior murals and stained glass, and Ted came in as park architect after Gilbert Stanley Underwood was fired by the Yosemite Park & Curry Company. Their work became known for its sensitive choice of building materials and inclusion in surrounding environments. (Even if you haven’ t been to Yosemite, you’ve seen representations of their work — the Overlook Hotel interiors in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining.)

Dinosaurs on the Bay

For over a year, the Skirballs and Spencer hashed out their concept until San Diego commissioners demanded to know what they had in mind. Spencer deadpanned that they were going to build a cable-driven dinosaur ride over the bay. They almost thought he was serious. After all, he was the dean of environmental architecture. In January of 1960, the Skirball brothers were awarded a 50-year lease by the San Diego City Council. Ted Spencer’s prospectus had won the day. No dinos, though.

Their $1.6 million “family vacation village” would be located on the island’s west side. Other developers’ proposals submitted to the Mission Bay Park Commission included a floating snack bar built on an old Navy barge and a fast-draw pistol contest range. Both were politely declined.

South Sea Dwellings from the Alps?

Ted Spencer’s pole construction technique — inspired by stilt houses of the Motuans from Papua New Guinea, and by prehistoric Swiss lake pfahlbauten (“pile structures”) built in the Alps from about 5,000 to 500 BCE — was chosen not for aesthetics only, but out of necessity. Just as Half Moon Inn and Bali Hai builders on Shelter Island had encountered, providing stable foundations on a sand-filled, man-made island required sinking poles down to bedrock. Designs would have to conform to the newly approved Mission Bay Park Master Plan — shake shingles and redwood siding with trim colors of white, charcoal, turquoise, and persimmon. The first to comply was Eugene Weston Jr.’s design for the Islandia Hotel (1961) in Quivira Basin.

In 1963, Vacation Village had its own golf course, later sacrificed for the addition of more bungalows. There is still a putting green at Paradise Point.

Under Spencer’s supervision, project architects included Daniel Osborne, Zachary R. Stewart, Valentino Agnoli, William A. Kibby, and Jeanette Dyer Spencer, interior design.

“Like ice stacked in a tall glass, they realize their fullest and happiest potential by complimenting a precise concoction of selected ingredients…”

— Architectural critic James Britton II on the elements of Vacation Village

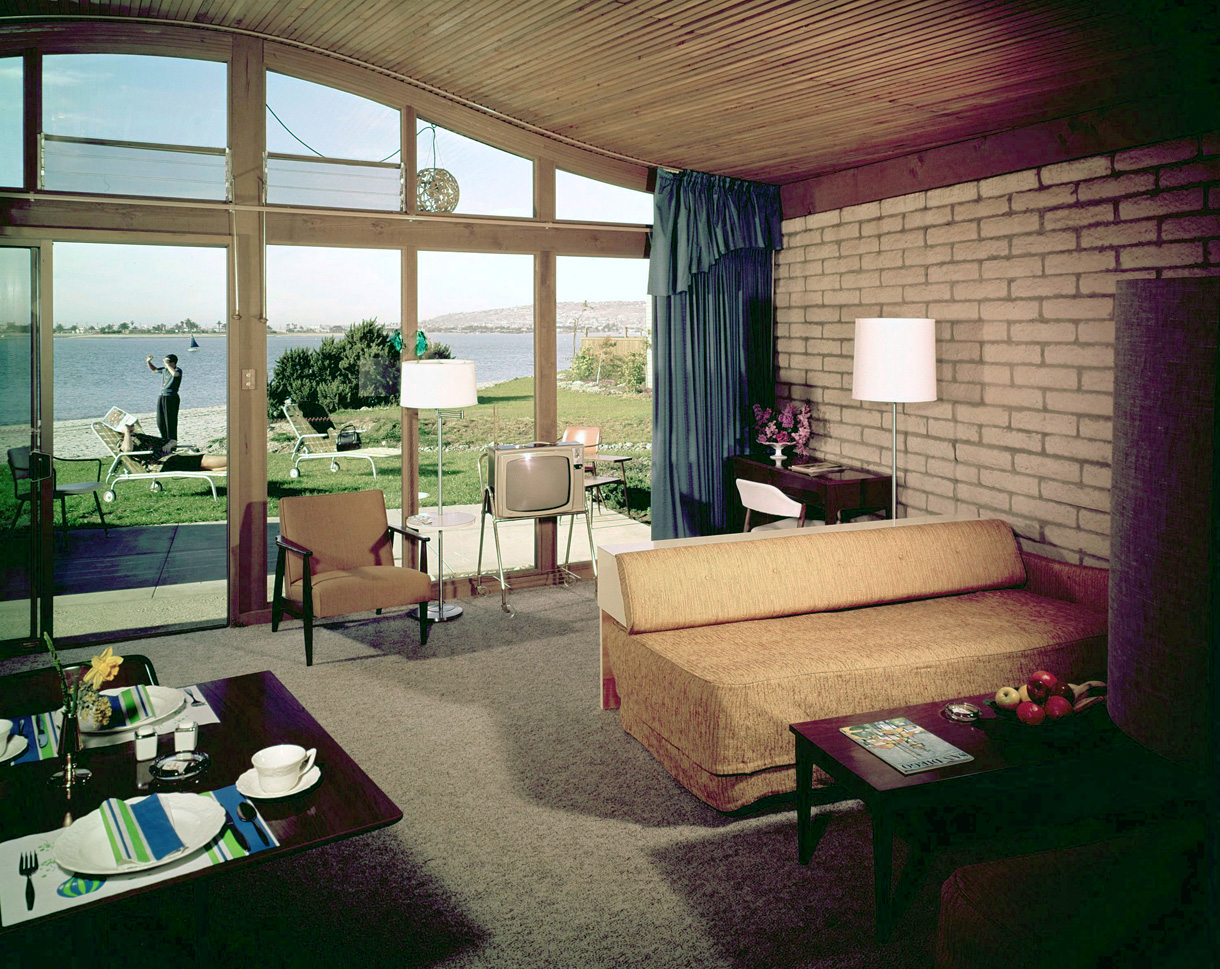

Spencer and Lee used modern technique, water, sand, and sky in combination with steel, wood, and concrete in Vacation Village’s seemingly simple design. It’s a mid-century modern pastiche of Chemonite-treated telephone poles, glass, rippling iron reinforcing-bar, shake shingle kiosks, pavilions, lagoons, and adobe bungalows scattered throughout the property. No hotel high-rise, but an observation tower that overlooks all of Mission Bay. Climb to the top that tower, and you’ll see the whimsical sculpture of a red-eared slider turtle designed and forged in iron rebar by Val Agnoli. Bob Golden of M.H. Golden Construction Company came on as builder-partner and figured out how to construct the damn thing. Ted Spencer even admitted that they were engineering as they built.

The wavelike rooflines of Vacation Village were meant to recall the ocean, interiors using a sea green and turquoise color palette with highlights in marigold and persimmon. Inside the main building, undulating latticeworks of iron bars were inspired by the curves of the 1925 wooden Earthquake roller coaster (now called the Giant Dipper) at Belmont Park in Mission Beach. Exposed laminated-wood construction and shake shingles were utilized throughout the main structures, pavilions, and kiosks.

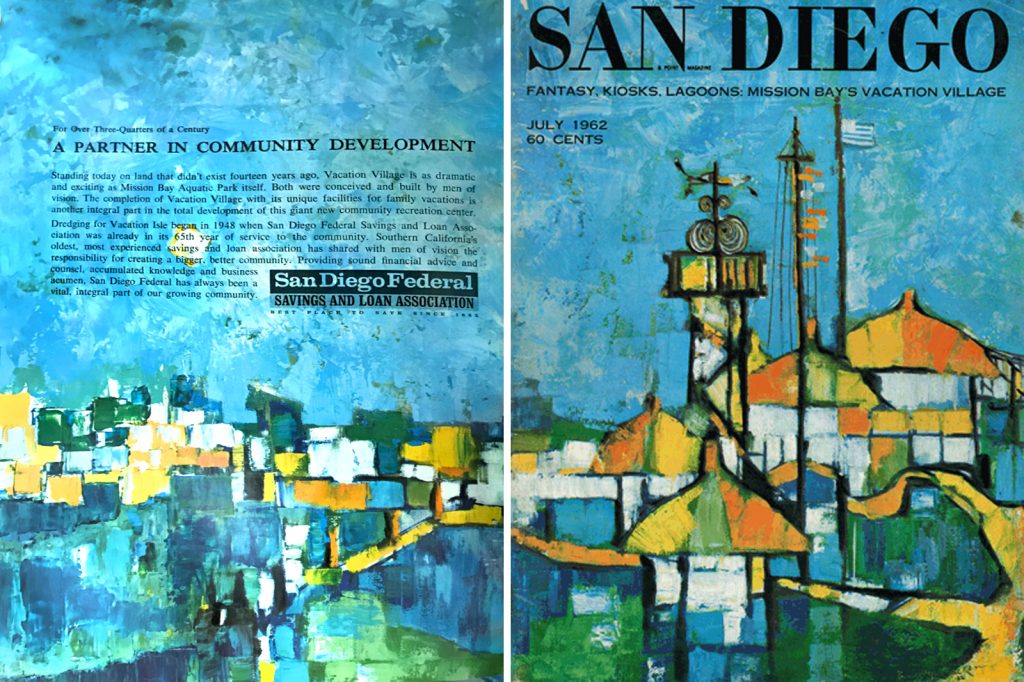

Vacation Village opened on June 16, 1962, to rave reviews: “There is a little of the Orient and a little, too, of once-virgin unspoiled America in the design and indigenous materials employed.” The Skirballs kicked off their grand opening with a family treasure hunt benefitting the Hospital Auxiliary Council of San Diego County. They advertised “101 Kinds of Fun at Vacation Village” and proceeded to list them all in the local newspaper. The island was still pretty barren. It would take years for landscape architect Frank Rich’s 600 types of tropical plants (from twenty countries) to mature.

But for guests’ accommodation and amusement, there were furnished bungalows with kitchenettes ($14-$37 a night), chef Andrew Pierides’ restaurant and tavern Jack’s Steakhouse (named for Skirball), snack shop, three swimming pools, a dock with small boats, rental bicycles, gift shop, a day camp for children headed up by San Diego Charger quarterback Jack Kemp, wooded glen, tidepool, an amphitheater, evening entertainment, shuffleboard, badminton, and croquet. Later came an 18-hole, par-3 golf course designed by Johnny Dawson. And yes, largemouth bass, bluegill, and trout fishing in the freshwater lagoon. If you don’t want to smell up your hacienda kitchenette, call room service. They’ll pick up your day’s catch, clean, and prepare it for dinner!

Interior of a bayside bungalow at Vacation Village. The July 1962 issue of San Diego Magazine is on the coffee table.

San Diego Magazine dedicated front and back covers and a major portion of the issue to Vacation Village.

“He’s a man of boundless energy who can do four or five things at one time… I don’t know when he sleeps!”

— A friend of Jack Skirball

The Skirballs, being showmen from Hollywood, included a few surprises of their own throughout the property — a porpoise fountain said to have been from a production of Cleopatra, film-prop masonry ornamenting bungalow entrances and a collection of twenty mission bells from El Camino Real. They even placed a pair of live toucans by the central lagoon to greet guests. (Until a teenager stole one from its cage to give to her boyfriend. It escaped her clutches — and promptly drowned in the lagoon. Skirball donated the widowed bird to the San Diego Zoo.)

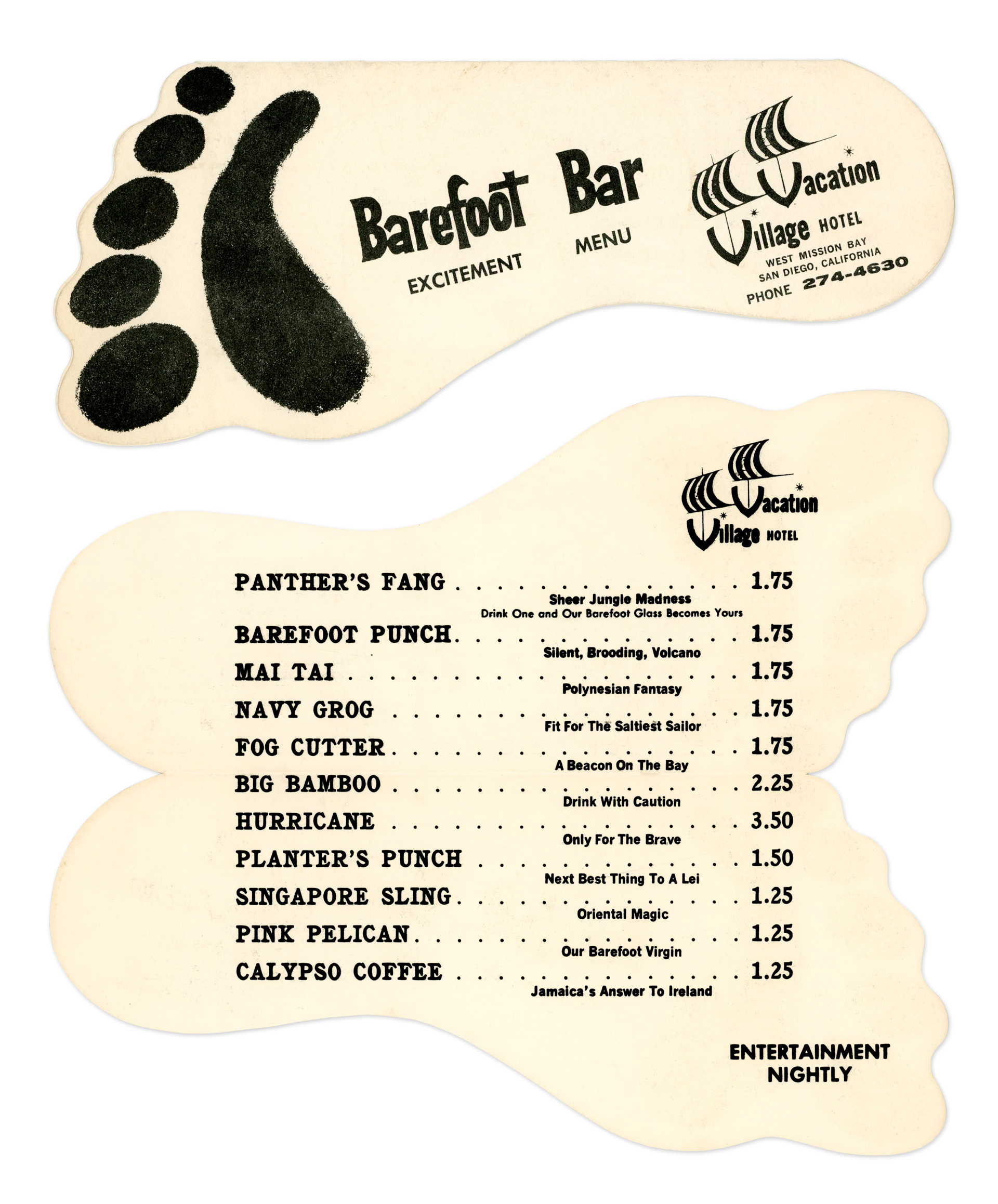

Known at the “Grotto” when built, Barefoot Bar could also stand in as a bomb shelter. Note the floating fish and footprints embedded in the ceiling.

Tiki Comes to Paradise

On the southern shore of the island stood a cocktail lounge initially called “The Grotto.” The bar was built right on the beach. Of subterranean concrete and telephone pole construction, it was built beneath a pile of sand and could double as a bomb shelter. The joke was you could “get bombed at the bar but not bombed from the sky.” For decades it was the Barefoot Bar, home of Calypso music, exotic belly dancers, and tropical drinks.

By the late 1979, the palms had grown up around Barefoot Bar, which transformed into Don the Beachcomber.

Until 1980, when there were a major renovation and expansion of the resort, and it became a Don the Beachcomber. “A lush South Seas atmosphere complete with wicker furniture, hanging baskets of plants, and bayside view is the setting,” wrote newspaperman Alan Page.

Don’s served Polynesian cuisine, plus the requisite Zombie, Fog Cutter, Scorpion, and Mai Tai. Cantonese food. Crab Rangoon. Waitresses wore floral miniskirts and hostesses, halter-tops. It was a favorite of many for Sunday brunch on the patio, with entertainment overlooking the bay. Bad timing, though — it was the era before the Tiki Revival of the 1990s. “Don the Beachcomber is charming enough from the outside, its rustic wooden building decorated with tikis, torches, and appropriate foliage,” wrote restaurant critic Leslie James. “But inside, it’s full of sticky Formica and sickly ferns. A few wicker chairs and ersatz rock gardens do not a Polynesian paradise make.”

Skirball sold the property in 1983 to P&O Enterprises (Peninsulas and Orient Steam Navigation Company of England), operator of The Love Boat. Vacation Village was renamed San Diego Princess Resort and heavily marketed as a vacation destination by the hotel and cruise ship operator. The ill-fated Don the Beachcomber reopened as the Polynesian Princess, but unfortunately, its food and drink suffered from the mediocrity so prevalent in corporate chain restaurants of the time.

What’s Next?

Good news came in 1998 when LaSalle Hotel Properties bought San Diego Princess Resort and reimagined it as Paradise Point Resort & Spa. Buildings were renovated and accommodations upgraded — there are five pools now. Their fine dining restaurant Tidal serves coastal cuisine, and they brought back the crowd-favorite Barefoot Bar. Moai statues still guard the property. Tiki torches abound.

And Paradise will soon transform yet again, into Margaritaville Island Resort.

West Mission Bay

Vacation Village / Barefoot Bar / Don the Beachcomber (1962-1984)

San Diego Princess Resort / Polynesian Princess (1984-1998)

Paradise Point Resort & Spa / Barefoot Bar (1998-2020)

Margaritaville Island Resort (2021?)

1404 Vacation Road

San Diego, CA 92109

Notes

Citation: Martin S. Lindsay. ‘Paradise Point and Vacation Village: a bit of Tahiti in San Diego.’ Classic San Diego: tasty bites from the history of America’s finest city. Web. < https://classicsandiego.com/hotels/vacation-village/>

A shortened version of this article first appeared in Baby Doe and Otto von Stroheim’s Tiki Oasis Guide Book, August 2020. https://issuu.com/ottovonstroheim/docs/2020_tiki_oasis_guidebk_small

“equal partners,” Jack Harold Skirball (1896-1985), was a rabbi, film producer, and president of Bowlero bowling alleys, He and his brothers were all involved with the motion picture industry from its early days. Joseph S. Skirboll (1879-1958), oldest of the Skirball brothers, served as Metro Pictures’ motion picture exchange manager, producer, and director. He died in San Diego. Ezra Richard Skirball (1889-1962), worked for Monogram Pictures. He died in San Diego right after Vacation Village opened. William Norman “Bill” Skirball (1886-1978), was co-developer of Bowlero, a film producer, yachtsman, and owner of a large chain movie theatres.

“Bob Hope,” is from Shirley Eder, “That’s show business,” The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 7 Jul 1974, pg 95; Bob Hope and Bob Thomas, The road to Hollywood: My 40-year love affair with the movies, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1977.

“Birth of a Baby,” information comes from contemporary newspaper accounts; Life Magazine, 11 Apr 1938; “Mrs. F.D.R. approves Life’s baby pictures,” The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), 18 Apr 1938; “Regent Theatre to show ‘The Birth of a Baby,’” The Ottawa Journal (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada), 9 Jun 1942; Felicia Feaster, Bret Wood, Forbidden fruit: the golden age of the exploitation film, Midnight Marquee Press, 1999.

“Mai-Kai restaurant,” is from “Realty roundup,” San Diego Union (San Diego, CA), 16 Aug 1959; “Realty roundup: Mid-city plan sparks projects,” San Diego Union (San Diego, CA), 29 May 1965; Frank Rhoades, “Reporter on the run,” San Diego Union (San Diego, CA), 19 Aug 1965; City of San Diego Zoning Department documents and Assessor plat maps, accessed 2017.

“Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo,” or João Rodrigues Cabrilho, was probably a Castillian Spaniard rather than Portuguese. Only one contemporary reference says he was Portuguese, all other references point to Spanish. (Unless he was Portuguese and kept it on the down-low. Soldiers could be tried as foreigners and have their wealth and titles stripped if discovered.) In 1521, Cabrillo was sent by the governor of Cuba to capture and return the rogue Hernán Cortez from Veracruz. Cabrillo’s forces were trounced, so he joined forces with Cortez, conquering Tenochtitlan, Oaxaca, and Guatemala. Cabrillo received several encomiendas for his services, and for decades made a killing in Guatemala and Honduras enslaving the indigenous to serve his soldiers, mine gold and build ships. See Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla. (A.G.I.) Sección Patronato, leg. 87, n 2, R 4. Información de los Servicios del General Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, 1617; W. Michael Mathes, “The Discoverer of Alta California: João Rodrigues Cabrilho or Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo?” Journal of San Diego History (vol 19, no 3), Summer 1973; Nancy Lemke, Cabrillo: First European explorer of the California coast, San Luis Obispo, California: EZ Nature Books, 1991, pp 104-108.

“twenty-five million cubic yards,” William B. Rick, “Mission Bay,” Journal of San Diego History (vol 48, no 1), Winter, 2002; San Diego Parks and Recreation Department, “Mission Bay History,” The City of San Diego, website accessed 7 Jul 2020.

“a pair of live toucans,” comes from “Valued hotel bird abducted, drowns” San Diego Union (San Diego, California), 1964.

“freshwater lagoon,” Elmar Baxter, “Take a weekend vacation,” Ford Times (vol 56, no 3), Mar 1963, pp. 24-27.

“porpoise fountain,” was one of the Hollywood flourishes Skirball reportedly added to his resort. Is it a porpoise, or a fish? Most references come from 50th anniversary articles, quoting press releases from either Paradise Point or San Diego Convention and Visitors Bureau. Various articles and press releases have cited the fountain’s origin to a silent film version of Cleopatra he produced; or the 1964 Elizabeth Taylor version of Cleopatra “which he produced.” I sat through all four-and-a-half hours of the latter, looking for it to no avail. Granted, there were many hours filmed left on the cutting room floor. Unless he was an uncredited silent partner in either, my research has not yet shown Jack Skirball produced any version of a Cleopatra film. Let me know if you know!

Thanks for the interesting article, and I was especially interested to see where the Mai Kai was supposed to go. I do not look forward to Margaritaville. Blecch.

Being a native San Diegan, the transformation of this iconic property makes me sick. I can only imagine the architecture being destroyed to allow for a cheap theme. This was always a family oriented resort and should remain that way.

I watched them build it

Now i see them tEar it down!!

Used to go there in the 70’S. WHAT IS IT NOW? WHERE CAN I FIND PICTURES? IS IT OPEN? WOULD LOVE ANY INFORMATION.

I KNEW THE CABINS – MEAL DELIVERY – PADDLE BOATS, HOBIE CATS – RESTAURANT – KID’s game room – ducks, geese bunnies

Could even take the dog! Many wonderful memories.

Yes, it is still open and called Paradise Point. Jimmy Buffet’s organization has purchased the property and it may eventually become one of their “Margaritaville” resorts. For more info, visit paradisepoint.com

Thanks for this time capsule!

This was the coolest hotel when I was a kid. We styed there ca 1962-65. Separate cabanas, beach and bicycles. At age 10 I learned about curry in the restaurant, starting a lifelong love of spicy foods.