The little shop in front at various times sold cigars, cigarettes and later became Kosher Kelly’s — hot corned beef and pastrami sandwiches for those sailors on the go.

Brothers Mike (Circus Dance Cafe), Hank (Circus Cafe, Milan Realty), and John Milan, born to Domenico and Maria Milan, all went into the bar business. Bocardo (Lincoln Hotel) and his buddy “Baldy” Ewing (Tropics, The Gay Nineties) were jokingly known as “the tavern tycoons.” Bocardo’s father, Anton, owned the Lincoln Hotel just south of the Cinnabar at 536 Fifth Street, padlocked by police in 1942 because Dolly Butler ran parts of upstairs as a rooming house for prostitution.

And also, because of their little “election fraud” problem…

In the 1930s, businessmen would register their residential addresses at the downtown hotel in order to vote for their buddies in the district, even though they lived elsewhere. Quid pro quo. Everyone was doing it! So Mike and Hank tried. A poll worker caught their prevarications, and the youngsters ended up on probation working in a day camp for a while.

That didn’t stop them from opening up the Circus Dance Cafe in 1934, fresh off the end of Prohibition. The Renaissance of circus- and clown-themed establishments was ramping up and reached its apex in January 1952, with the release of Cecil B. DeMille’s spectacle, The Greatest Show on Earth. It was that year’s highest-grossing film and won the Best Picture Oscar. Emmett Kelly, whose sad hobo clown character dominated the real Ringling Brothers Circus for 14 seasons though 1955, even made an appearance in the film. In San Diego, notable venues included the Circus Room at Hotel del Coronado (1937), the Circus Room bar in the Chi-Chi downtown (1946-1952), the Circus Room in Pacific Beach (1952-1974), among others. Not to mention Oscar’s Drive-ins, featuring Oscar, the clown chef. Named after its founder Robert Oscar Peterson’s dad, Oscar W Peterson, the chain would go on to become Jack-in-the-Box.

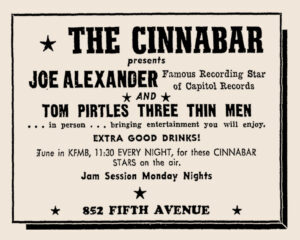

In 1952, Sid and Evelyn Peritz owned the Cinnabar. “They bought it from a very prominent man named Abe Kahn… He owned Bradley’s, he owned the Texas Liquor stores, he owned quite a few things,” reminisced a regular. “There were lots of marines and sailors, and later on the navy wanted the sailors to stop going there… they couldn’t do a thing about it.” Abraham J Kahn was a Prohibition bootlegger and father of San Diego developers Irvin, Julius and Yale Kahn.

Check out those prices at Abe Kahn’s Texas Liquor House. Photo, California Neon Products Collection.

It had become a well-known bar for the then-mostly closeted gay community. So much so, San Diego and the Cinnabar in particular were viciously portrayed in muckrakers Jacquin Lait & Lee Mortimer’s tell-all, USA Confidential (1952). Lait was a veteran journalist and editor at the New York Daily Mirror who had little tolerance for anything or anyone who did not espouse conservative McCarthyism.

“The fairy fleet has landed and taken over the nation’s most important naval base. We are hard characters; shocked by nothing, but what we saw in San Diego frightened us. Picture a sailor burg, plentifully supplied with bars, cocktail lounges, and strip-joints, all equipped with B-girls and other hussies, and yet the sea-dogs seldom come. The lonesome broads sit by themselves, moodily getting drunk alone, while the fairy dives roll merrily. There are dozens — packed every night. Young sailors queue up in the street — waiting their turn to get in.”

The term B-girls was short for bar girls, “farm girls that had followed their boyfriends in the service here” to the San Diego hospitality bars, who’d snuggle up to customers to drive more liquor sales, and many times, extra services. And gay bars had their b-boys…

“There is nothing anywhere as disgusting as the Cinnabar, in the 800 block on 5th Avenue. Its waiters are prancing misfits in peekaboo blouses, with marcelled hair and rouged faces. They flirt and make love with sailors, competing with the B-boys, a switch on an old institution. These sit at the bar, solicit drinks, kiss and pet customers. At the Cinnabar, dates are made for assignations elsewhere. For those in a hurry, jobs are performed in the men’s rooms and telephone booths. Even one bouncer, a six-foot 200-pound giant, looks queer.”

Some straight regulars in denial were offended by the book. “The Peritzes never allowed that, that never went. That didn’t go then. That never happened in the Cinnabar. And there wasn’t any room for it. The authors exaggerated to make the book more interesting.” Although this right-wing hate piece was a bestseller, Lait didn’t enjoy its success for much longer. He became bedridden for 18 months and went into a coma before he died in 1954.

The Famous Door

By 1953, the Peritzes changed the Cinnabar to The Famous Door, a jazz club with continuous music and jam sessions every Sunday — as a nod to New Orleans’ Bourbon Street joint of the same name (the oldest continually open jazz club in the United States). “When we bought the place,” remembered Evelyn in 1996, “it was the Cinnabar. We changed it immediately, from that. It was a gay bar. We changed the name to the Famous Door and changed the clientele.” Sid was killed that year when his small plane crashed, and Evelyn ran it for ten years after. “We had very good clientele,” insisted Evelyn. That may have been the case, but others remembered the bar still as a safe haven for the gay community. And a target for continual police harassment. “They’d close the place down, and they’d put on the front of it ‘Raided Premises.’ That’s what happened to the Famous Door, the Cinnabar, Mary’s Place, and some others. There was a time in the early ’50s when the length of a gay bar’s life in this town was about 30 to 50 days.”

“Thursday nights they had talent nights,” recalled a regular named George in 1996. “They would give $25 for the first award and a bottle of champagne for the second. The girls from the burlesque down on F Street used to come in and they would perform up on the stage. Can you imagine? It was quite a place. Anybody could come in and get up on the stage…”

The Famous Door got busted for employing “B-girls” and degenerated into a go-go girl bar by 1965. “Wanted: go-go girls to do the ‘Watusi,’ ‘Swim,’ and ‘Twist.’” ($2.75 an hour.) And then a massage parlor. Some may remember going there to the Sushi dance space in the 1980s. Today, it hosts The Onyx Room dance club. [2025]

Gaslamp Quarter

Cinnabar (1942-1953)

852 Fifth Avenue

San Diego, CA 92101

Notes

In addition to the Cinnabar Club, Billboard’s 1944 Leading Cocktail Lounges included Cafe LaMaze, El Cortez Skyroom, La Jolla Beach & Tennis Club, Patrick’s, Pirate’s Cave, The Show Boat, The Silver Slipper, and Top’s Cafe, “Leading Cocktail Lounges,” The Billboard 1944 Music Yearbook, pg 324; “tavern tycoons” is from the San Diego Union, in a 1949 article naming Bocardo and Jack “Baldy” Ewing as San Diego’s “tavern tycoons;” Christy Gregg, “Straight from the Shoulder,” San Diego Union, 24 Nov 1949; According to US Census enumerations, John Anthony Milan (1907-1963) Hank and Mike’s brother, worked as a bartender for their places; Judith Moore, “Mafia in San Diego in Early 1950s,” San Diego Reader, 19 Dec 1996; Matthew Licona, “Hillcrest, Homosexuality, History,” San Diego Reader, 10 Jul 1999; Randy Dotinga, “SD Confidential: Inside a Lost Gay Past of ‘Fairy Dives,’ Raids and a Fallen Admiral,” in Voice of San Diego, 15 Jul 2016.

Onyx Building

Onyx Room (1987 – 2025)

Sushi Performance Gallery (1981-1987)

The Famous Door (1962-1972, Mr & Mrs Roy McGrath)

The Famous Door (1953-1962, Sidney Peritz)

Cinnabar Cafe (1942-1953)

El Trojan Cafe (1939)

Trojan Bar (1934)

852 Fifth Avenue

San Diego CA 92101